Advertisement

HOW DID ALFRED TARSKI SOLVE THE LIAR’S PARADOX, AND WHY DOES IT MATTER ?

In order to explain how the “liar’s paradox” was solved, it is first helpful to understand what the liar’s paradox is; I will later discuss why its solution was important.

The liar’s paradox can be stated very simply. Each of the following statements qualifies as an instance of the liar’s paradox:

1. This statement is false.

2. I am a liar; I always lie, and I am lying now.

3. The sentence on the back of this shirt is false./The sentence on the front of this shirt is true.

There are countless other ways of stating the liar’s paradox, but the important part is understanding why “the Liar” – as it is called by Philosophers – is paradoxical; this is not always evident to students who are new to the problem, as I have frequently received confident assertions that the statement is true, or that it is false, sometimes in the same class, which leads to interesting arguments.

Let us begin with a brief assessment of what it means for a statement to be “true.” In order to avoid a lengthy digression on the subject of truth (which I have discussed elsewhere), let us satisfy ourselves by saying that if a statement or proposition is true, then it portrays the world in the way that the world actually is. We could say that true statements assert facts, but, unfortunately, we are living in the age of “alternate facts.”

Given that true statements portray the way the world is, consider statement 1 above: “This statement is false.” If the statement is indeed false, and if the proposition asserted in 1 above is correct in saying that statement 1 is false, then statement 1 is true. It is true because it tells us something about statement 1 which is accurate or correct, i.e., given the way the world is, statement 1 is false. But wait! if statement 1 portrays its own falsehood accurately, then statement 1 is true. After all, that’s what truth is, a statement which portrays the world accurately.

To reiterate, statement 1 says that it is, itself, false, and if it reports to us accurately, then statement 1 must be true. But it says that it is false, and yet, if is tells us correctly of its own falsehood, then it is true. If statement 1 is true, then it is false, and if it is false, then it is true. It is easy to see how the same problem arises with similar statements like “I always lie.”

As interesting as this quirk of logic may be (it was discovered by Medieval logicians about 1,000 years ago), is it in any way important, or is it just one of those interesting thought experiments of which philosophers are so fond? Until the 20th Century the Liar was indeed just an interesting quirk of logic, but with the 20th century comes the digital computer and artificial intelligence. Suddenly the Liar becomes very important. But why?

There is an episode of the original Star Trek (the title of which I unfortunately cannot recall) which illustrates the problem very well. The Enterprise discovers a civilization which has been dominated by a computer for countless centuries. The computer was originally created by ancestors who wanted to eliminate suffering among their descendants. The inhabitants of this planet lead reasonably pleasant lives, but they are not free, which of course strikes the crew of the Enterprise as problematic. Near the end of the episode the computer poses a threat to the Enterprise, the exact nature of which I cannot recall.

Advertisement

However, Spock, who has been studying the computer very carefully, makes the following statement to the computer: “I always lie, and I am lying now.” The computer tries to process the statement but, of course, cannot determine whether it is true or false. As a result, the computer falls into an infinite logic loop, locks up, and is rendered non-functional. I believe there are explosions, but that part is not particularly realistic.

The problem, however, is very realistic. If a statement of the Liar-type is made to a computer, the computer could indeed enter into an infinite logic loop. Unless the Liar is somehow solved, the digital computer would not be possible. (Note: to the best of my knowledge, Tarski knew little about computers; he tackled the Liar simply because he thought he saw a solution to it, and for all practical purposes, he was right.)

In order to solve a problem, it is first necessary to diagnose the problem. So, what causes the “liar’s paradox” in the first place? Tarski concluded that the Liar is the result of language’s ability to talk about itself; I will call this “the self-referential capacity of natural language.” Languages which can talk about themselves (and this includes all known natural languages) are considered to be “semantically rich.” In order to eliminate the Liar, one need simply remove the ability of natural language to refer to itself, i.e., eliminate its semantic richness, impoverish the language in a certain sense.

Tarski did this by dividing “natural language” into two unnatural parts. The first part is the “object language” which can talk about anything in the universe, except itself. If it becomes necessary to talk about the object language, then this will require the second part, a “meta-language.”

The meta-language can talk about anything in the universe, including the object language, but the meta-language cannot talk about itself. If, in turn, it becomes necessary to talk about the meta-language, then this will require a “meta-meta-language,” which can talk about anything in the universe including the object language and the meta-language, but the meta-meta-language cannot talk about itself. If it becomes necessary to talk about the meta-meta-language, then it will require another “meta-level,” and so on as long as is necessary.

Those who are familiar with computer science will recognize the idea of having languages which occur in “levels.” The elimination of Liar-like paradoxes is the reason for this layered structure in machine languages; because of this structure, a digital computer cannot be trapped into a Liar-induced infinite logic loop. However, there is a trade-off; machine languages are “impoverished” relative to natural languages which do, in fact, possess the capacity for self-reference. This point, i.e., the relative impoverishment of machine languages, becomes a matter of some concern when we are discussing “artificial intelligence” or “artificial consciousness.”

Be that as it may, I suppose we can be thankful that the evil computer encountered by the Enterprise was not designed by Tarski.

Advertisement

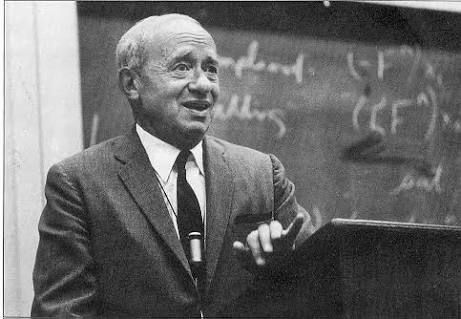

Alfred Tarski (January 14, 1901 – October 26, 1983), born Alfred Teitelbaum was a Polish-American logician and mathematician of Polish-Jewish descent. Educated in Poland at the University of Warsaw, and a member of the Lwów–Warsaw school of logic and the Warsaw school of mathematics, he immigrated to the United States in 1939 where he became a naturalized citizen in 1945. Tarski taught and carried out research in mathematics at the University of California, Berkeley from 1942 until his death in 1983

Advertisement